A majority of Americans have heard about companies creating data profiles, and it’s common for those who have to see ads based on their personal data" />

A majority of Americans have heard about companies creating data profiles, and it’s common for those who have to see ads based on their personal data" /> A majority of Americans have heard about companies creating data profiles, and it’s common for those who have to see ads based on their personal data" />

A majority of Americans have heard about companies creating data profiles, and it’s common for those who have to see ads based on their personal data" />

Today, it is possible for companies, advertisers and other organizations to take users’ personal data from a variety of sources to create detailed profiles based on someone’s likes, preferences and other characteristics. This survey finds the majority of Americans have heard or read about this concept, and those who have think all or most companies are using profiles to better understand their customers. Among those who are familiar with profiles, a majority reports seeing these ads on a somewhat regular basis.

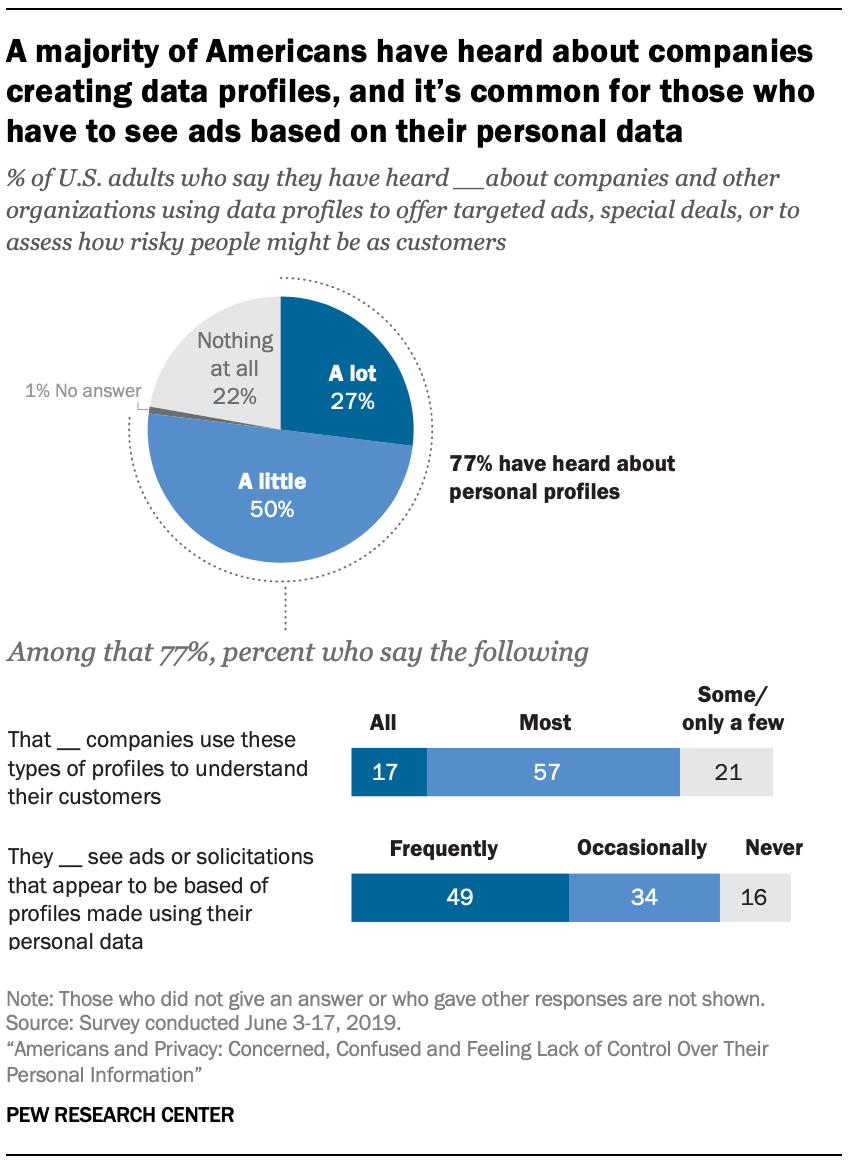

Overall, the public is familiar with the practice of companies and organizations using an individual’s experiences and personal data to create detailed user profiles. Most Americans – 77% in total – say they have heard at least a little about how companies and other organizations use personal data to offer things like targeted advertisements, special deals, or to assess how risky people might be as customers, including 27% who say they have heard a lot about this concept. About one-in-five adults say they have heard nothing at all about this practice.

Survey respondents were shown the following prompt: “Today it is possible to take personal data about people from many different sources – such as their purchasing and credit histories, their online browsing or search behaviors, or their public voting records – and combine them together to create detailed profiles of people’s potential interests and characteristics. Companies and other organizations use these profiles to offer targeted advertisements or special deals, or to assess how risky people might be as customers.”

Not only are most Americans aware of this concept, they routinely see them in practice. Roughly eight-in-ten adults who are familiar with these profiles say they occasionally (34%) or frequently (49%) see ads or solicitations that appear to be based on a profile made of them using personal data. Put another way, 64% of all U.S. adults report seeing these types of ads or solicitations.

Awareness of these data-driven profiles is relatively widespread across a range of demographic groups, but college graduates and more affluent adults are especially likely to be familiar with both the concept of profiling and the outcome – advertisements apparently targeted at them. Adults with a bachelor’s degree or higher are more likely than those with a high school education or less to say they have heard about personal profiles (87% vs. 69%) or to say they see advertisements that appear to be based off their personal data (93% vs. 73%). Similar patterns are present by household income, with those living in higher-income households being more likely to say they are familiar with the term and that they see these types of ads than those living in lower-income households.

Respondents who say they have seen ads based on their personal data were asked a follow-up question about how much they understood about the data collection associated with such targeted advertising.

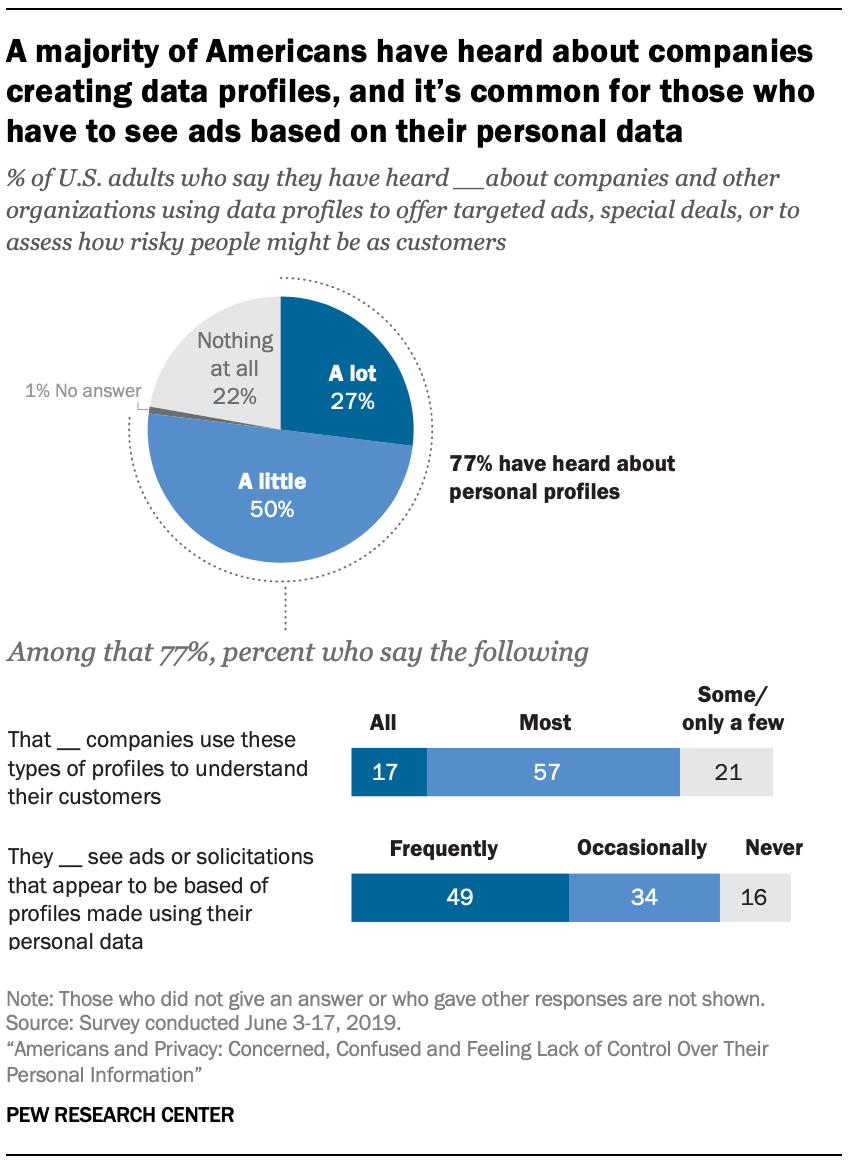

Fully 64% of adults who have ever seen ads that appear to be based on their personal data say they at least somewhat understand what personal data is being used to create targeted advertisements, with 14% saying they understand a great deal. Still, some ad-seers are less sure about the concept: 35% say they understand not much or at all the type of personal data being used to create these ads. When all American adults are considered, 41% say they understand what data is used to create these ads.

Additionally, a majority of ad-seers think these types of ads accurately reflect who they are. Around six-in-ten adults who see these ads (61%) say they accurately reflect their interests and characteristics. Still, relatively few in this group – just 7% – say these ads accurately reflect who they are very well. (The share who say these ads reflect them at least somewhat well is 39% among all U.S. adults.)

Personal data is used for a range of purposes by companies and the government. The findings reported in Chapter 2 show that Americans express general concern about the data collected but that the public finds some uses more acceptable than others. This diversity of thought is evident when adults consider some of the purposes of the data collection.

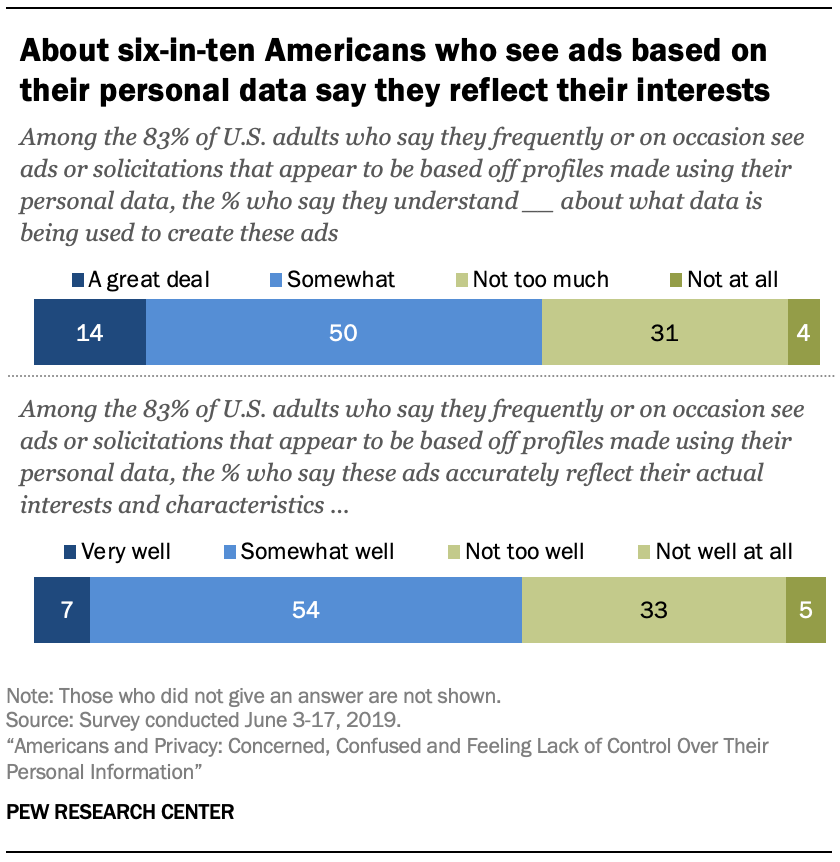

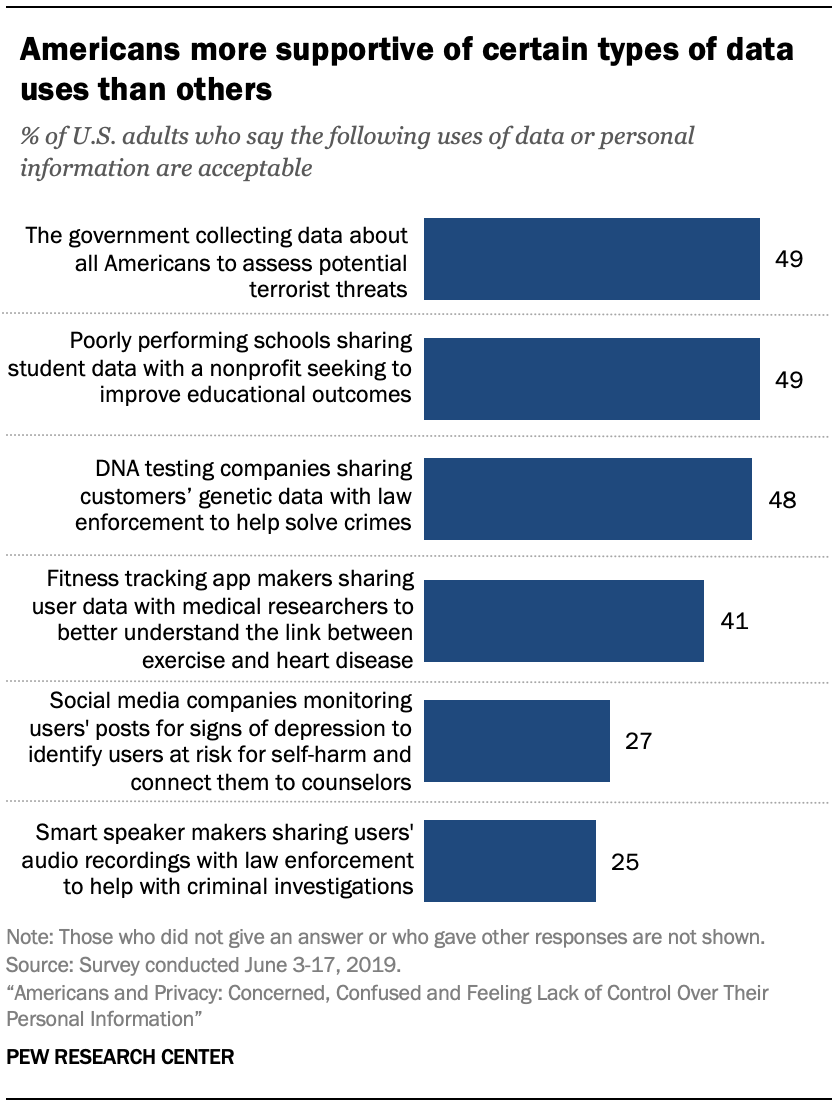

When asked whether it was acceptable or not for a poorly performing school to share student data with a nonprofit group in an effort to improve educational outcomes, roughly half of Americans (49%) say they consider this to be an acceptable form of data sharing. The same share of the public also believes it’s acceptable for the government to collect Americans’ data to asses who might be a potential terrorist threat.

Additionally, a similar share of Americans (48%) think it’s acceptable for DNA testing companies, like AncestryDNA and 23andMe, to share their customers’ genetic data with law enforcement agencies in order to help solves crimes.

Still, other forms of data collection are deemed less acceptable by the public.

About four-in-ten adults (41%) find it acceptable for makers of fitness tracking apps to share user data with medical researchers to better understand the link between exercise and heart disease, compared with 35% who say this is unacceptable.

And just 25% of Americans find it acceptable for the makers of smart speakers to share audio recordings of their customers with law enforcement to help with criminal investigations. A similar share (27%) finds it acceptable for a social media company to monitor users’ posts for signs of depression in order to identify individuals at risk of self-harm and connect them to counseling services. In these scenarios, 49% and 45% respectively say they are unacceptable forms of data use.

But even as Americans’ assessments of these practices tend to differ by the type of data being collected and the purpose of its use, at least 20% of adults say they are unsure about their acceptability in each of these specific scenarios. For example, 27% of adults say they are unsure if social media companies checking users for signs of depression in order to get them help is acceptable or not, and 24% say the same about low-performing schools sharing student data with nonprofits.

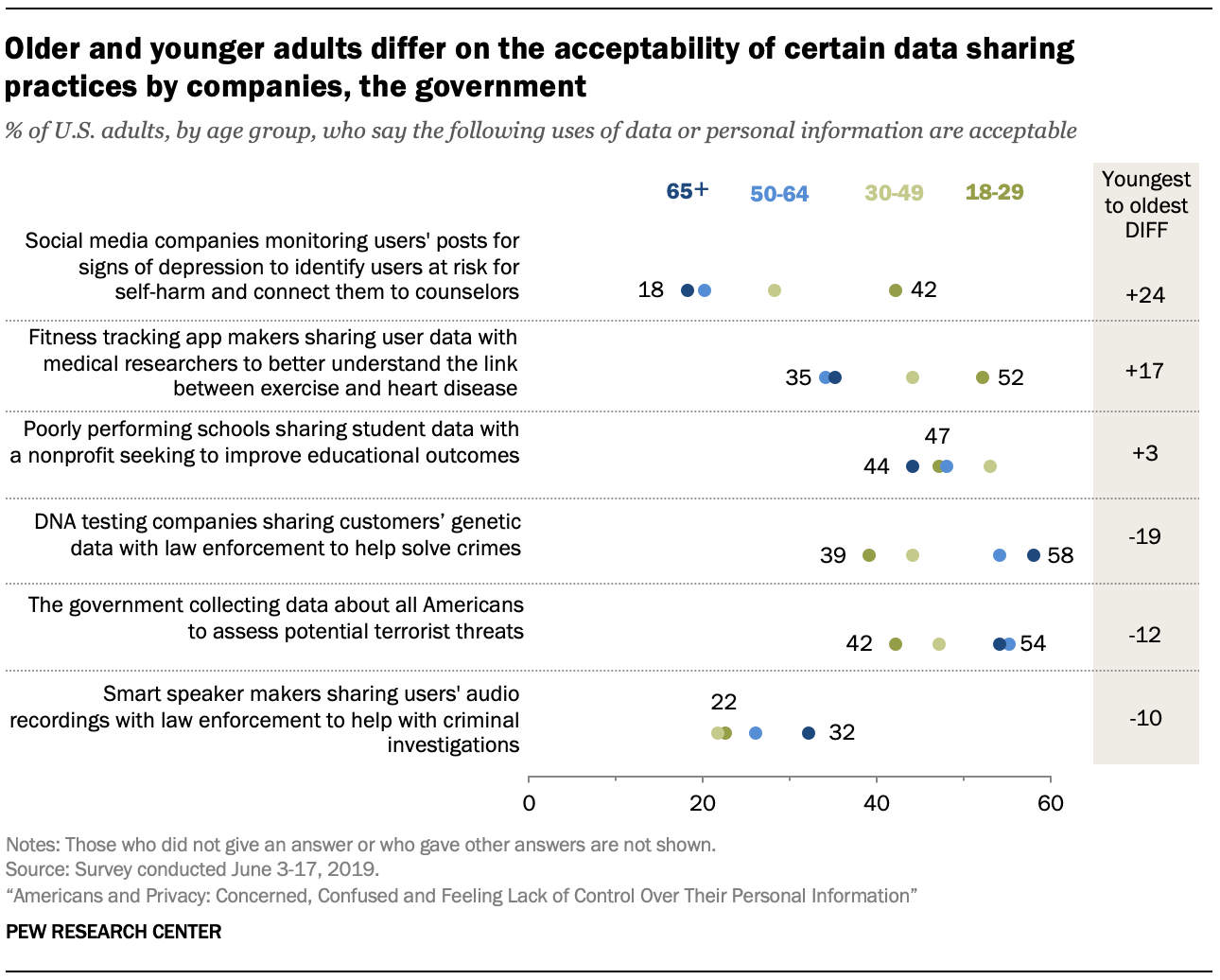

The public’s views on whether certain types of data use are appropriate tend to differ by age. Adults ages 18 to 29 are more likely than those 65 and older to say it is acceptable for makers of fitness tracking apps to share data with medical researchers to better understand the link between exercise and heart disease (52% vs. 35%) or for social media companies to monitor user posts for signs of depression so they can identify people at risk of self-harm and connect them to counseling services (42% vs. 18%).

But there are other instances in which older groups are more supportive of data sharing. Roughly six-in-ten adults ages 65 and older (58%) say it’s acceptable for DNA testing companies to share customers’ genetic data with law enforcement to help solve crimes, compared with 39% of those ages 18 to 29. Older adults are also more likely than younger adults to believe that the government collecting Americans’ data to assess terrorist threats or makers of smart speakers sharing audio recordings with law enforcement to help with investigations is an acceptable form of data use. However, attitudes about schools sharing student data with a nonprofit are relatively similar, with 44% of those 65 and older finding this acceptable, compared with 47% of those 18 to 29 who say the same.